Revealing Passwords

It’s evening in the cellblock. Things are fairly quiet. It was a long day. Many had visits from their lawyers, a few got released; most of them finished their sentence on Thursday, but Friday was a holiday and due to the slow administration, they only got released today, Monday evening.

We had a new arrival too. It happens most days. The routine is the same: the “capo” introduces the procedures and most people say hi, then he’s left alone to adjust for a while. Most have a dazed expression, like they still don’t really believe this is happening. Some cry, later, in the dark of their cells. I remember the feeling when first arriving here, I guess I have adjusted, but it’s still not easy.

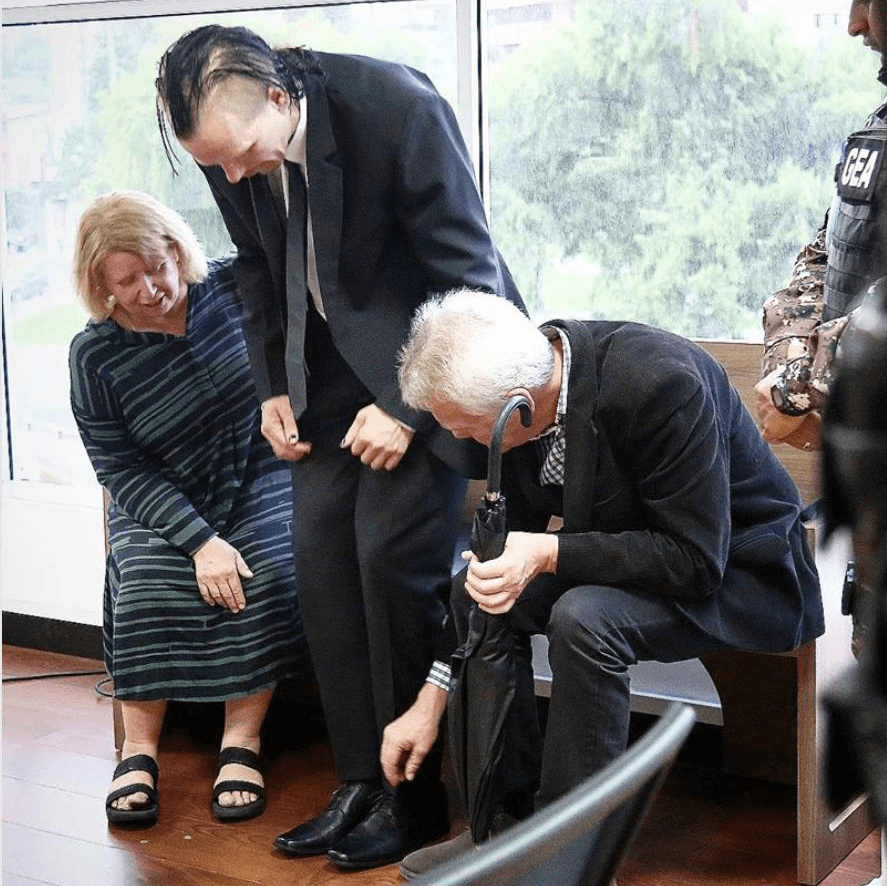

A week ago we had a hearing with the prosecutor and the technical forensics people, the people that are ripping apart and dissecting my whole digital life.

They asked if I would help them and voluntarily give them my passwords, so they could inspect the content of all my devices. I said no.

Now, saying no is a bit of a luxury. In many jurisdictions around the world, I could have been held in contempt for refusing to provide passwords. I don’t remember and I don’t have any internet access so I can look it up, but the sentences for not providing passwords can be long. I still would have said no.

I also, on purpose, never use any of the fancy biometric stuff that Apple has, for example things like Face ID and Touch ID. I don’t trust these technologies and especially Touch ID is tricky from a legal standpoint. Most jurisdictions allow prosecution or police to take your fingeprints. That means you can be forced to unlock, even if you wouldn’t be forced to give up your passcode. Same thing with facial recognition.

There are many reasons I’m not interested in submitting to the prosecution’s request. The first, and simplest, is that I don’t recognize or accept their legal authority. They have not revealed what they think I have done; when, how or where. They have no evidence and they have placed me in prison without any proper justification. That is a travesty of justicy and anyone that takes part of this scam loses any legal authority they otherwise would have had.

I can’t stop them from imprisoning me, but I certainly don’t acknowledge their right to do it.

However, even without that reason, it would be very hard for me to comply with such request. There are two reasons for that. The first is that I believe in privacy as a human right. That means you can’t just turn it off when it’s inconvenient. It’s a right that should be built into the foundations of our society, and in the meantime, both corporate and government surveillance is getting closer and closer to all-powerful. What we have inside our skulls is intimately connected to what we have in our devices and I believe that’s where the line has to be drawn.

But what about bad people? That’s the immediate question everyone asks. The answer is pretty simple. Law inforcement has more power to investigate than ever in history. That will have to be enough. In the US, the 4th amendment protects against unreasonable searches and from my perspective, searching through devices is clearly unreasonable. We are still supposed to have a presumption of innocence.

The other reason is simple. My devices contain conversations with other people. If I revealed my passwords, I would allow the Ecuador prosecution the possibility to invade the privacy of all my friends, family and coworkers. That is clearly not ethically accceptable. The forensics lab will certainly try to break into my devices. They will probably succeed with some, especially if they use black market or “gray market” tools for the Apple devices, although it likely would be expensive, but at least I’m not complicit in this immoral, illegal action.

It is time for us to establish clear lines around our digital lifes. If we don’t, political interests will, and the results will not be for our liking.

May 6th, 2019

Ola Bini